Talismán

November 14 - December 4, 2020

Pt.2 Gallery

1523b Webster St.

Oakland, CA 94612

November 14 - December 4, 2020

Pt.2 Gallery

1523b Webster St.

Oakland, CA 94612

The flowers began to take over my body, but it wasn't until later that I realized that my grandmother wasn't

the only person who could see them. My mom and aunts also noticed but never said a word to me. They explained

that they didn't want to scare me. It was a secret amongst those who could see, understand, and connect to

the spiritual world. It was the Gift of Seeing.

the only person who could see them. My mom and aunts also noticed but never said a word to me. They explained

that they didn't want to scare me. It was a secret amongst those who could see, understand, and connect to

the spiritual world. It was the Gift of Seeing.

Read the short story that accompanies the exhibition here.

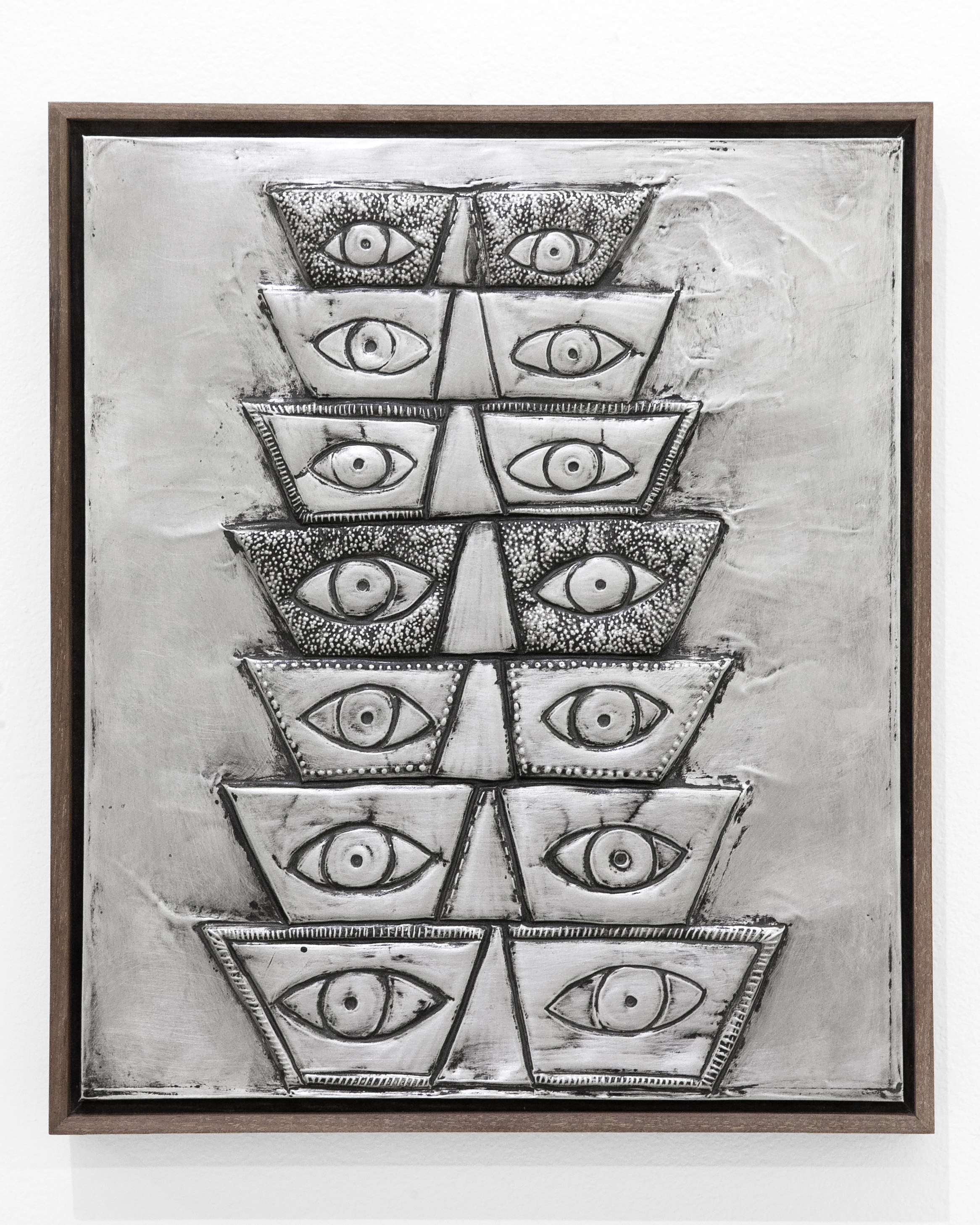

Marcus Garvey wrote that “a people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.” Hernandez’s new work has an archival quality that draws on the importance of artwork to document moments in history. The artworks in Talismán explore the dual belief systems from Hernandez’s upbringing in Mexico, that of the Catholic Church, and visits to the temple of the Espiritismo Trinitario Mariano. They thus not only offer self-reflection for the artist, but an essential preservation of knowledge.

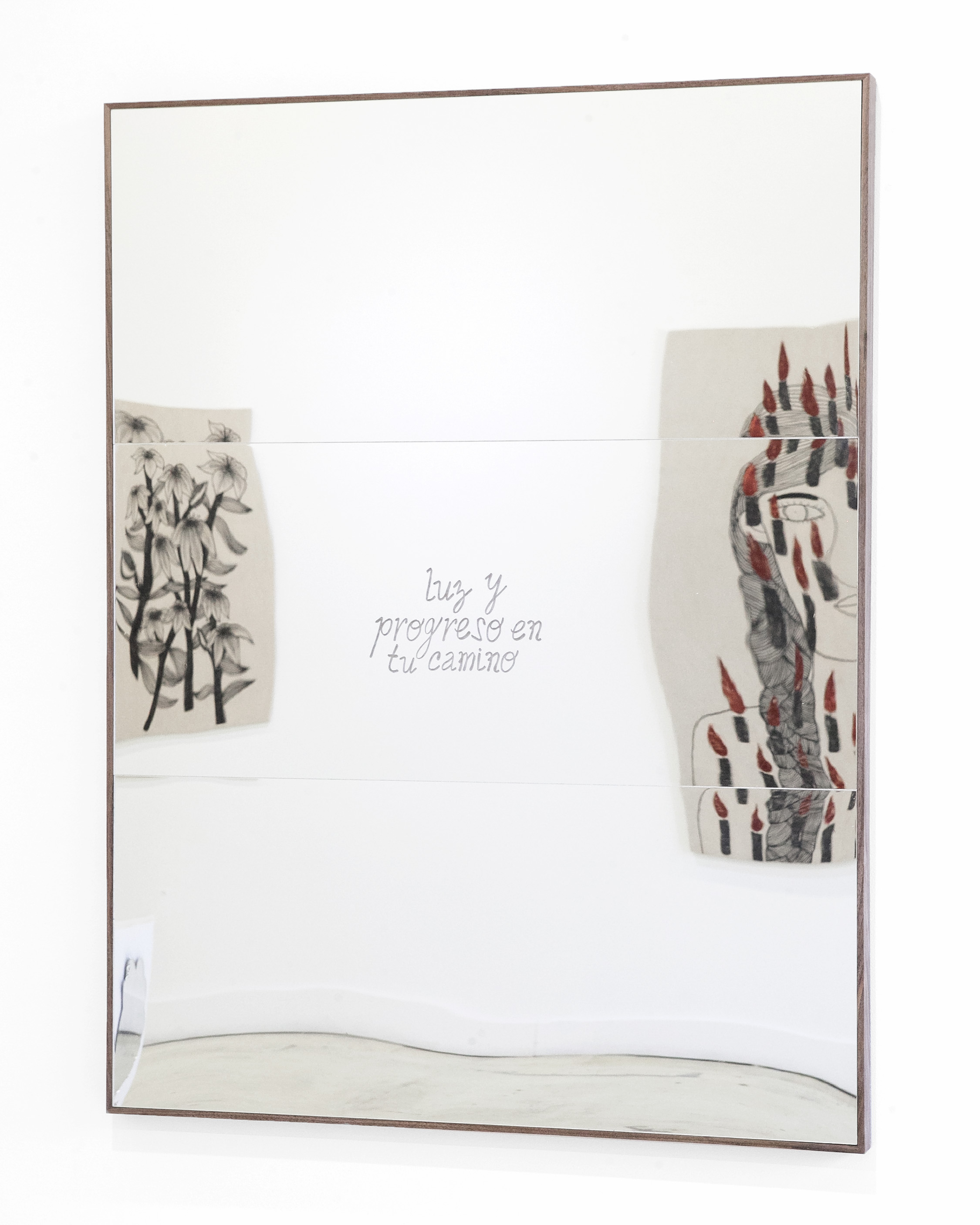

Three portraits grace the exhibition, one in paint on a clay-covered canvas, the other two in ceramic, awash in medallions. While these self-referential works are not entirely self-portraits, they represent the range of Hernández’s experiences between her belief systems. In the painting Culpa (Guilt), dozens of candles obscure the figure’s forlorn expression. For Hernandez, these burning candles are indicative of the burning guilt she associates with her rigid Catholic upbringing. While the painting acknowledges outside pressure, the busts portray differing forms of inner desire. One bust, representative of Hernández’s Catholic side, is covered in metal milagros. These charms are placed on representations of differing saints in a church as a form of wish making. The other bust, portraying the same visage, is covered in flowers. These flowers denote the relationship between the natural world and the universe, uncontrollable by humans. The spiritists believe that the body is of no importance, as it is a temporary vessel of the soul. These works, among Hernandez’s first to reference the human form, denote the importance of the believer, both in body and in soul, as part of a ritual.

Three portraits grace the exhibition, one in paint on a clay-covered canvas, the other two in ceramic, awash in medallions. While these self-referential works are not entirely self-portraits, they represent the range of Hernández’s experiences between her belief systems. In the painting Culpa (Guilt), dozens of candles obscure the figure’s forlorn expression. For Hernandez, these burning candles are indicative of the burning guilt she associates with her rigid Catholic upbringing. While the painting acknowledges outside pressure, the busts portray differing forms of inner desire. One bust, representative of Hernández’s Catholic side, is covered in metal milagros. These charms are placed on representations of differing saints in a church as a form of wish making. The other bust, portraying the same visage, is covered in flowers. These flowers denote the relationship between the natural world and the universe, uncontrollable by humans. The spiritists believe that the body is of no importance, as it is a temporary vessel of the soul. These works, among Hernandez’s first to reference the human form, denote the importance of the believer, both in body and in soul, as part of a ritual.

Both in ceramic and on canvas, these latest works by Hernández indicate an aesthetic shift from her brightly colored, super flat acrylic paintings. Her ceramics are cast without glaze in an earthy ochre tone, while she builds up modeling paste on canvas only to sand it away.

The atemporal qualities garnered by such techniques present Hernandez’s works as artifacts, contemporary renditions meant to preserve a treasured history at risk of being lost to the sands of time. As Hernández says: “The idea of creating a way to document this way of seeing life has been crucial to me in these moments where our mortality has become even more fragile. My most significant motivation is to note the way many of the women in my family existed between these two religions.”

The atemporal qualities garnered by such techniques present Hernandez’s works as artifacts, contemporary renditions meant to preserve a treasured history at risk of being lost to the sands of time. As Hernández says: “The idea of creating a way to document this way of seeing life has been crucial to me in these moments where our mortality has become even more fragile. My most significant motivation is to note the way many of the women in my family existed between these two religions.”

Hernandez’s exhibition comes at a time of transition - one in which the desired outcome may not meet reality. In these moments, when the threads of time escape our control, we turn to talismans like milagros to influence either our fate or that of the world at large. Hernandez’s figures, in ceramic and on canvas, are covered in talismans.

To the ancient Greeks, the word talisman meant “I complete a rite.” This definition emphasizes the importance of the believer rather than the physical object itself in a ritual. Whatever form they take, whichever desire or wish they may represent, whichever belief system they may derive from, these talisman’s are but a physical manifestation of the soul.

To the ancient Greeks, the word talisman meant “I complete a rite.” This definition emphasizes the importance of the believer rather than the physical object itself in a ritual. Whatever form they take, whichever desire or wish they may represent, whichever belief system they may derive from, these talisman’s are but a physical manifestation of the soul.

Written by Luc Sokolsky.